Cooperative living is an idea that comes and goes throughout history. In its simplest expression, cooperative living is a bunch of roommates sharing a big apartment, each person getting a room of their own and then sharing the expenses of things like food, internet service, etc. For most of the 20th century, cooperative living was not popular on a mass scale because it looked too much like communism.

Back in 1902, though, Good Housekeeping published an account of a cooperative kitchen in a suburb near Chicago. The account is interesting because cooperative kitchens are a logical idea that never really caught on.

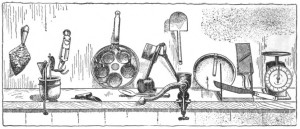

This particular cooperative kitchen was located in a house specifically rented by the cooperative group. The group was made up of ten families that included about fifty people in total. The idea was that a hired cook would cook for all the families in the rented kitchen, and the families would eat in the dining room attached to the kitchen (families supplied their own tables). The families committed to eating all of their meals in the cooperative dining room, paying about $18 per month to do so. By doing this, the families would not have to cook their meals, purchase groceries, or plan their meals—all of that would be done by the cook hired by the cooperative.

The author of the article made it clear that this all was something of an experiment, and that the conditions at this suburb in Chicago would probably not carry over to other locations. The group’s finances, in particular, were something of a best case scenario. The cook they hired lived in the neighborhood and happened to be unemployed at the time. The space they rented was actually rented from one of the group’s members, who moved upstairs into her house and just lived in the upstairs. Although the group’s charter stipulated that meals should cost $.30 per person per day, the actual cost was about $.32 per day, and members had to pay extra at the end of the month.

Cooperative living in general has a poor track record–people usually like to go their own way on things. The problem with the cooperative kitchen idea is that in order for it to work, members needed to eat there for every single meal. This is something like committing to go to a certain restaurant for every meal. Sometimes it is nice to just sit at home and eat, and sometimes what is offered may not be that appealing.

Americans tend to be individualistic, and this may be why cooperative kitchens have never really caught on. There was a minor push for them in the early 20th century, but this was usually as a way to prepare cheap food for the poor. The Good Housekeeping article is significant in that middle-class people were doing it for themselves, but it most likely did not last very long. We have something of a love-hate relationship with our kitchens, and making a commitment to eat at one place for every meal is probably too much for most people.

Source: Milton B. Marks, “The Longwood Co-operative Kitchen,” Good Housekeeping, February 1901, 101-103