I like looking through old magazines, and while paging through a copy of The American Kitchen Magazine, from October, 1902, I saw an article about kitchen designs that made me think about how kitchens have changed over time.

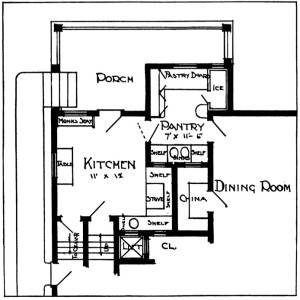

The article featured two kitchen designs, the graphic for one of which is below. Simply looking at the graphic brings out a few differences between then and now. The kitchen is effectively separated from the rest of the house–no open floor plan here–which makes sense. The defining feature of most kitchens was the stove, and in 1902 most stoves still burned wood or coal, although the gas stove was making inroads. The great thing about the gas stove was that the fire went on or off in an instant, keeping the kitchen from becoming overly warm, but for most people the wood or coal fire kept the kitchen uncomfortably hot for much of the year. Kitchens were usually located at the back of the house, and many families went a step farther and constructed a summer kitchen in an outbuilding. The design below included a flue above the oven, both to take away fumes from the stove and also to take away cooking heat.

Taking the idea of separation a step further, the kitchen is broken up into two areas: a kitchen and a pantry area, which could be separated by a swinging door. The main function of the pantry was to hold groceries, but it also included a pastry board for making pastry. Putting the pastry board in a separate room made sense because the heat from the oven might melt the butter in the pastry as the dough was being handled.

Another major difference between this kitchen and the kitchens of today is the lack of countertop space. Some shelves are included, particularly around the stove, but one entire wall in the kitchen has only a table and no countertop. Reading the article brings out another difference in the shelves: they are to be covered with zinc, with the zinc running two inches up the wall where the shelves join the wall. The pastry board, in contrast, was to be a solid glass slab, which would probably help keep the dough cold while making pastry.

This kind of kitchen design was completely reworked by the middle of the 20th century. Kitchens were moved to the front and center of the house, which had a more open floor plan, so mothers could cook and watch children at the same time. Air-conditioning and the popularity of gas and electric stoves, not coal or wood stoves, made it so the heat from the kitchen was much less of an irritation. Zinc and glass were cast aside as building materials for other man made and natural materials, and countertops and cabinets grew to cover all the walls in the kitchen. Many old houses are still around with this kind of floor plan in the kitchen, and while they are charming they can also be somewhat annoying to actually cook in.

Source: Nina C. Kinney, “Two More Kitchens,” The American Kitchen Magazine, October 1902, 14.